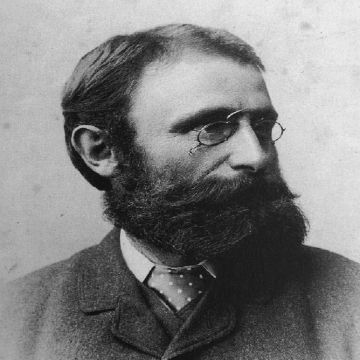

James Hardiman

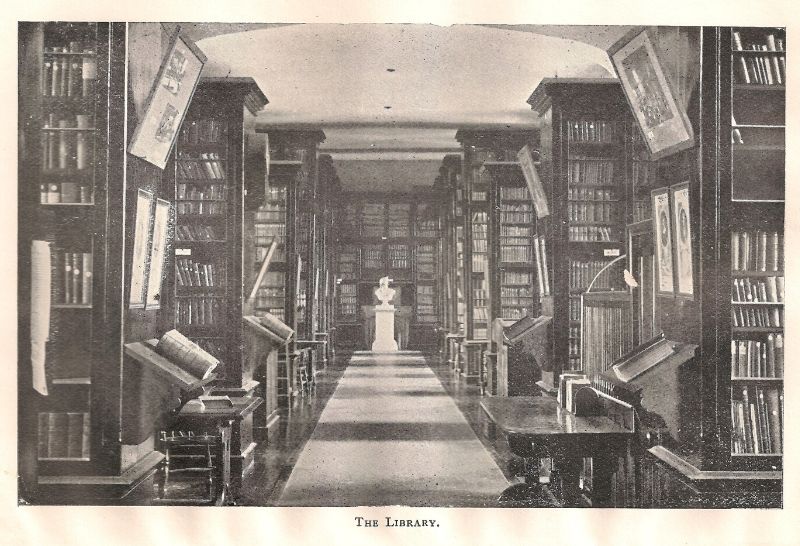

“We have endeavored, as far as the limited sum permitted, to provide the Library with those works most essentially necessary in the different branches of learning. Many departments are still not adequately provided for.”

At Christmas 1849, his friend, the antiquarian John O’Donovan (1809-1861), asked Hardiman in a letter whether he had “procured any books for the ‘godless’ library?” This was a reference to the fact that the country’s Catholic bishops had frowned upon the establishment of the Queen’s colleges as “godless colleges”!

From the President’s reports over the next few years, it would seem that Hardiman had plenty of difficulties to contend with as Librarian. The college’s buildings were not being completed and funds were insufficient for the purchase of necessary equipment and materials. Things seemed to improve somewhat after Hardiman’s death in 1855: the 1856 report of Dr. Edward Berwick, who had succeeded Kirwan as President, specifically mentions the library and its improved state, and the “stillness and order which prevail showing that the readers are evidently bent upon the acquisition of knowledge!”